The Preface to The Prophecies (also called the “Letter to Cesar,” Nostradamus’ newborn son) is 10 pages long (1568 Lyon edition, pages 3 through 12). It is relative easy to read, in the sense that the language made sense, even though what appears to be ‘sentences’ (determined by period marks) seem to go on, taking a long time to end. Comparatively, the Epistle to Henry II is 21 pages in length (1568 Lyon edition, pages 3 through 23 of final three Centuries). This uses much the same, relative to easy to read French and Latin, but because this letter is more deeply explaining what the quatrains reveal, he uses metaphor and symbolism that is difficult to grasp. Add to that confusion the appearance of ramblings (long ‘sentences’ again) that seem to be addressing one lucid point, before suddenly off that point and careening into some wildly new direction; and the Epistle to Henry II sounds like a senile old man writing a letter with no ability to stay focused on why he was writing a letter.

All of this is solved by reorganizing the Epislte to Henry II into a meaningful order. That reconstruction has to follow rules (rather than guesswork); and I have been led to realize the division rules are relative to the use of punctuation marks, such as period marks, colons, ampersands, and the combination of two marks of punctuation together, most commonly being a comma mark followed by an ampersand. According to the syntax of English (as my English teach taught me), both a comma mark and an ampersand are used instead of the written word “and.” To then place the marks “, &” together symbolically stated “and and,” which is bad writing grammar. I see this as where one line segment ends with a comma mark, so it can be joined to another line segment that has verbiage in agreement. The ampersand then breaks off that line segment, to be connected to another line segment that agrees with it.

This is simply how to divide the Epistle to Henry into puzzle pieces (like the quatrains are all puzzle pieces), which needs to be rearranged in an agreeable manner. That then means the words written can be discerned; but those also have rules to follow, in order for them to make sense, as intended. My work (over years) with The Prophecies led me write the book The Systems of Nostradamus: Instructions For Making Sense of The Prophecies, which teaches a divine syntax that must be learned, so fluency can come with understanding The Prophecies. I wrote this book focus on understanding Nostradamus, but the same systems of reading can be applied to Biblical Scripture, so a deeper truth arises from those Holy Scriptures. It is then the first true textbook for understanding Nostradamus and all divine and holy writings.

Relative to understanding those rules of divine syntax, questions about the meaning of The Prophecies can be answered, coming from the explanations given in the Letter to Henry II.

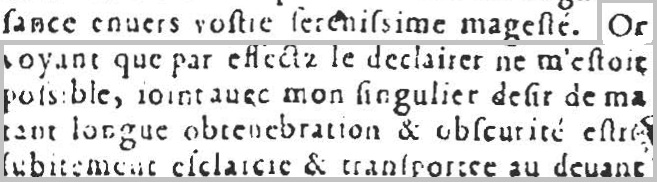

From the bottom of page 3, in the 1568 Lyon edition, for the letter to Henry is found.

The text to focus on now is placed within a gray outline. That says: Or voyant que par effectz le declairer ne m’estoit possible , joint avec mon singulier desir de ma tant longue obtenebration & obscurité estre subitement esclarcie & transportee au devant

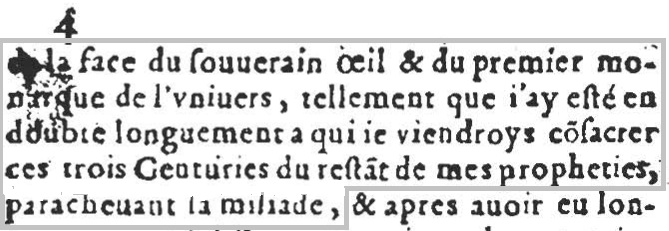

As there is no punctuation ending that page (after devant) this continues onto the top of page 4.

This continues to a focus that ends with the word milade“. The text in this gray outline continues to state: en la face du souverain œil & du premier monarque de l’univers , tellement que j’ay esté en doubte longuement a qui je viendroys consacrer ces trois Centuries du restant de mes propheties , parachevant la miliade ,

By realizing punctuation marks are signals to separate the text into segments of word statements, those segments are not difficult to understand, based on the rules of grammar that apply to French (which can be modified to follow rules that translate into English). This is an example of how line segments are important to read separately from one another, such that lucidity comes when agreeable segments create a flow of intelligible thought. Thus, the above translates into English saying:

Now seeing that through works him to declare not myself been possible ,

joining with my singular desire from my in such manner continual act of obscuring

& hidden meaning in words to be suddenly cleared up

& transported with him in front of upon there face of it sovereign eye

& from the premier monarch to the universe ,

in that fashion that I have been in suspect at length in which I may approach to consecrate unto these three Centuries from the remainder of my prophecies ,

finishing the thousand of ,

—–

Take note that an ampersand introduces three line segments. This seems to be repeating the word “and” excessively, like when one is poorly educated and feels a need to interrupt his train of thoughts with needless words like “you know what I mean?” In the verse of the books of the New Testament (the Greek texts of the Holy Bible) there are a plethora of uses of kai (9039, according to Strong’s). Some are so frequently used in the same chapter that it sounds like Stuttering John of the Howard Stern show trying to spit something out. So many “ands” make you want to scream, “Just say it!” However, kai is like an ampersand in The Prophecies, where there is no word attached to that symbol. It is a statement that says, “Importance to follow this mark. Pay close attention to what is written.” That is a hardfast rule of divine syntax; and it intensifies the meaning one sees, simply from that recognition.

With an ampersand introducing “hidden meaning in words to be suddenly cleared up,” that becomes an important line segment to understand. So, what does it mean where Nostradamus wrote?

“hidden meaning in words”? (obscurité)

“transported with him in front of upon into there face of it sovereign eye”?

(transportee au devant en la face du souverain oeil)

“the premier monarch of him universe”? (du premier monarque de l’univers)

According to Randal Cotgrave and his 1611 dictionary, the French word obscurité translated into English as “obscurity, darkness, dimness, cloudiness, duskiness, an overcasting; closeness, covertness, diffusedness;” and what can be seen as deeply applying here (following an ampersand) “a mystical sense, or hidden meaning in words.” For Nostradamus to explain his writings as “mystical” and “hidden meanings” that are “to be suddenly cleared up” (estre subitement esclarcie), this says understanding was always there, just beyond one’s ability to see that clarity.

This is the importantly stated “to be sudden cleared up” when one’s soul has come (ampersand use) “before” or “transported” or “carried over, removed fom one place to another” spiritually, so one’s soul is “with him “before” or “in front of” the divine presence of Yahweh, as His Son reborn, “with it” Christ Mind then leading one’s intellect. This is a presence “upon” or “into” one’s soul, so one’s soul is “with him” (du = de + le, reading le as a pronoun, rather than a meaningless article) that is Jesus, “removed from a state of physicality to one of spirituality.” This takes one to a union within one’s flesh, as “there” Jesus is king or High Priest of one’s bodily tabernacle. so one’s “face” is then the “representation” of one born again fom above as Jesus returned to human flesh. This is the gift “of he” that is Yahweh, to a committed servant in divine marriage, where Yahweh is the One God with “none superior” and the soul of Jesus is the “prince” of peace, whose kingdom is not of the material world, but the spiritual. This means Jesus becomes one’s “high” connection to the all-seeing “eye” of Yahweh. To discern the truth of The Prophecies, one must be led by Jesus. Nostradamus was so led to write that work; and to understand what he wrote, the same divine presence must leads one’s mind.

This then says that Jesus, like the Father as the Son, is the “first” and only Son, whose soul was created to be joined with all souls that seek Salvation. Jesus is then the “monarch” or “absolute prince” of one’s soul, acting as the Spiritual Lord that commands a soul in its body of flesh to act divinely. This presence makes on a Saint; and, according to the talents listed by the Saint Paul, a Prophet is the product of this divine presence, just as understanding a Prophecy is also. This means a Saint is motivated to act as commanded by the divine Jesus, so one does not put one’s light under a barrel to keep it from others, because Yahweh sends His Son’s soul to be “with” servants that minister in Jesus name, going into “the universal world” with a message of Salvation that is “he universal” to all souls.

Those three important line segments (all introduced by ampersands) tell that understanding The Prophecies demands full and total commitment to Yahweh, so one can be reborn as His Son Jesus “into” one’s soul, with the “face” of Jesus being the halo around Sants depicted in medieval artwork. This helps support that The Prophecies are not predictions, but the “divine utterances of Prophets.”

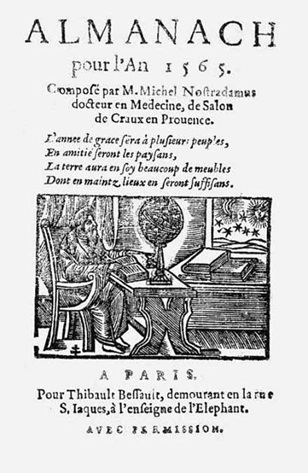

Continuing on in this from the top of page 5 is Nostradamus then explaining this final edition that was published in 1566. For a letter dated June 27, 1558, that says it was written eight years before it was first printed publicly. That means the Epistle to Henry II (King of France) was meant to be included, like a preface to Centuries 8, 9, and 10. That is stated when he then wrote:

“I may approach to consecrate unto these three Centuries from the remainder of my prophecies”?

(“je viendroys consacrer ces trois Centuries du restant de mes propheties“)

The word consacrer means “to consecrate, hallow, dedicate, or devote unto” (Cotgrave, 1611). That speaks in the voice of Jesus within Nostradamus, where je is not the man Michel de Nostredame but the presence of the soul of Jesus. Only a divine presence, such as the Son of Yahweh, can speak in the first-person, as “I” who is “to consecrate” that contained in this additional imprint. The word viendroys should be read as an Old French variation of viendrais, which is the first-person conditional form of the verb venir, meaing “would come, arrive, approach, draw near unto; proceed, issue, be drived from; spring, prove, grow; and to happen, chance, or fall out” (Cotgrave, 1611). To then state this “dedication” is placed upon “these three Centuries,” the number “three must be read as a statement about a “trinity,” which means the “three Centuries” or “three groups of a Hundred” quatrains all have been infused with the divine presence of Jesus within Nostradamus. When Centuries is read separately, as an important word (due to capitalization) the plural number applies to all of the “Centuries” of The Prophecies, as all are a work of the Trinity. These “three Hundred quatrains” are those “from” the whole that was written before the first edition was published in 1555, such that “these” represent the “remainder of” all produced through the Prophet Nostradamus, where “my” is the possessive pronoun relative to “I” (je), as the “prophecies” of Jesus, written by the hand of Nostradamus.

Nostradamus then ended this set of cohesive line segments with this statement:

“finishing here thousands of” (“parachevant la miliade“)

Here, this makes the statement of completion, as “finishing, consummating, accomplishing, achieving, and making an absolute end of” this work that is The Prophecies. It can equally be a statement that the life of Nostradamus on earth will soon be over, with his work for Yahweh, through Jesus “accomplishing” his ministry in the name of Jesus. The word la cannot ever be read as a meaninglsee feminine article, as “the.” It must always be read as the adverb là, meaning “there” or “here.” As “there was used earlier, “here” becomes supportive that Nostradamus “here” alive in the flesh is in his “finishing” days. The word milade is not a known word, as spelled. It then acts to show how words also must be divided so they make sense, where miliade divides into milia de, where milia is Latin for multiple “thousands” (plural) and de is a preposition meaning “of, to, with,” or “from.” This implies a “thousand” quatrains in ten Centuries, but the word can mean there are “countless” (as metaphor for a large number) examples “of” other divine Prophecies (the books of the Holy Bible certainly includes, but those apocryphal as well) these now “finishing” can be added to.