All Material Copyright of Katrina Pearls

(apart from the obviously stolen stuff)

Reproduction by Permission Only

When one realizes that Nostradamus explained The Prophecies was a work written so that

the words have double meanings, it becomes a simple matter of relinquishing all personal

desires to translate in solute oratione solely as “in plain prose”. Doing so rejects the use of

the word amphibologique in explanation, or recognizing it as a word indicating such

multiplicity of meaning. To see translations that are “not amphibological” is to find only

ambiguity.

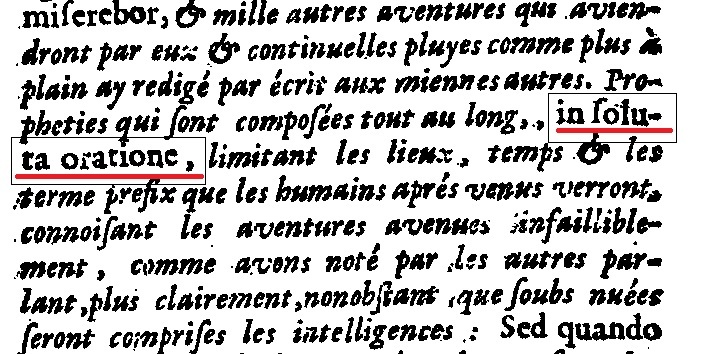

This means that a review of the complete context surrounding this Latin phrase has to also be

checked for amphibological wording. As such, we find that Nostradamus wrote, in his

preface, “comme plus a plain j’ay redige par escript aux miennes autres propheties qui

sont composes tout au long, in solute oratione, limitant les lieux, temps“. This literally

translates to read, “like more to smooth (or plain) I have reduced by writing (or set down in

writing) with (or of, to, in) them my other ones prophecies which are composed (or done in

verse, or written) ones all in the long (or length, or tedious, or out-stretched), in unrestricted

style [of language or speech] (or in free prose), limiting the places, times”.

Just from reading through these words, we can see Nostradamus referring to multiple

prophecies. This is based on the plural ending on mienne and autre, which shows another

set of multiple prophecies are known to be from the pen of Nostradamus. This multiplicity is

then the source of the multiple possibilities, as far as in solute oratione is concerned. As a

separated grouping of Latin words, they can be read as a recognized idiom, and they can be

read with the flexibility of each word being free to follow the extent allowed for the meaning of

the individual word. The standard translation would then be a reference to the other

prophecies, like in his Almanacs. They were written in standard understandable language,

much like prose. However, the words of The Prophecies were not designed to be read in

such a standard manner, which causes them to be unintelligible. This means, as a reference

to The Prophecies, and not the Almanacs, Nostradamus is making the statement that they are

written in unrestricted style (of language).

In this series of words, another such idiom is placed, which also follows the same

amphibological way to find whole meaning to the words. This is where Nostradamus penned

the word redige. In modern French, this word is plain and simple, accepted to mean, “written,

or drawn up,” as a written contract. In modern French, the word “reduire” is the verb meaning,

“to reduce,” with the past participle being “reduit.” It is obvious that Nostradamus did not

write “reduit,” which leads one to believe, “j’ay redige par escript” means, “I have drawn up,”

or “I have written,” rather than, “I have reduced.”

Well, in 1611, when a preserved Old French to Old English dictionary was written, the past

participle “redige” was stated to translated as, “reduced, brought back or into; digested,

ordered; urged, or compelled unto.” The same basic translations were also listed for

“reduire,” “reduict,” and “reduit.” In fact, the author of that dictionary, Randal Cotgrave, made

note that the idiom, “redige par escript” (the exact phrase written by Nostradamus) can

translate to mean, “set down in writing”. This would lead one to believe the evolution from two

words having the same multiple meanings, to two words with separate meanings was

beginning, but not yet complete. Therefore, Nostradamus is making the statement, “like more

to smooth I have set down in writing (or drawn up in writing) in my other prophecies [the

Almanacs, etc.] which are composed ones all in the length.” But, he is also stating, “like

[adding] more to [the words] plain [without other words in combination with each] I have

reduced [cut out what standard speech adds in] by writing [The Prophecies] with my other

prophecies [the Almanacs, etc.] which are understandable ones [because] all [of those

quatrains are worded] in the [standard form of prose in] long [form]”.

What this was conveying was nothing new. It was the philosophy made public by William of

Ockham, who was a master of the philosophy of logic, while also being a Franciscan friar, in

the 14th Century (he died 206 years before The Prophecies was first published). William is

perhaps best known for his philosophical argument called Occam’s Razor. A simple

description of this philosophy is, “less is more.” According to Wikipedia’s definition, “The

principle states that the explanation of any phenomenon should make as few assumptions as

possible, eliminating those that make no difference in the observable predictions of the

explanatory hypothesis or theory.” However, the paradox is that the essence of Occam’s

Razor is, “Plurality ought never be posited without necessity.”

For The Prophecies the necessity becomes plurality due to the bare presence of individual

words, which cannot be joined (for conversation understanding) until that plurality is

understood. This means a language without the singular restriction of syntax (not

amphibological) is the only way to the true meaning of The Prophecies, with all ambiguity

removed.